Home >>

The life and work of Stephen Frederick Gooden C.B.E., R.E., R.A. (1892 - 1955)

Stephen Gooden was an artist and engraver, mainly on copper. Much of his best work was done for the Nonesuch Press or George Harrap and Co., but he also designed bookplates for Kings, Queens, Princesses, friends and family. In addition he designed a small number of original engravings which show his fertile imagination and skill as an engraver. Here you can find:

► A table of his designs for bookplates, award labels and coats of arms

► A page showing some of his designs for bookplates and book labels

► A page showing some of his designs for arms and devices

► A page showing some of his designs for title pages and book illustrations.

► A page showing some of his engravings.

► A page showing some of his designs for bank notes

► A page of miscellaneous engraved designs, such as letterhead paper for bills and correspondence

► Update on 21/10/2023: Revised the numbering of bookplates to use the catalogue created by the collector Duncan Andrews, which I hope to get published with a biography of the artist. It will take some time as Andrews' catalogue needs to be transcribed.

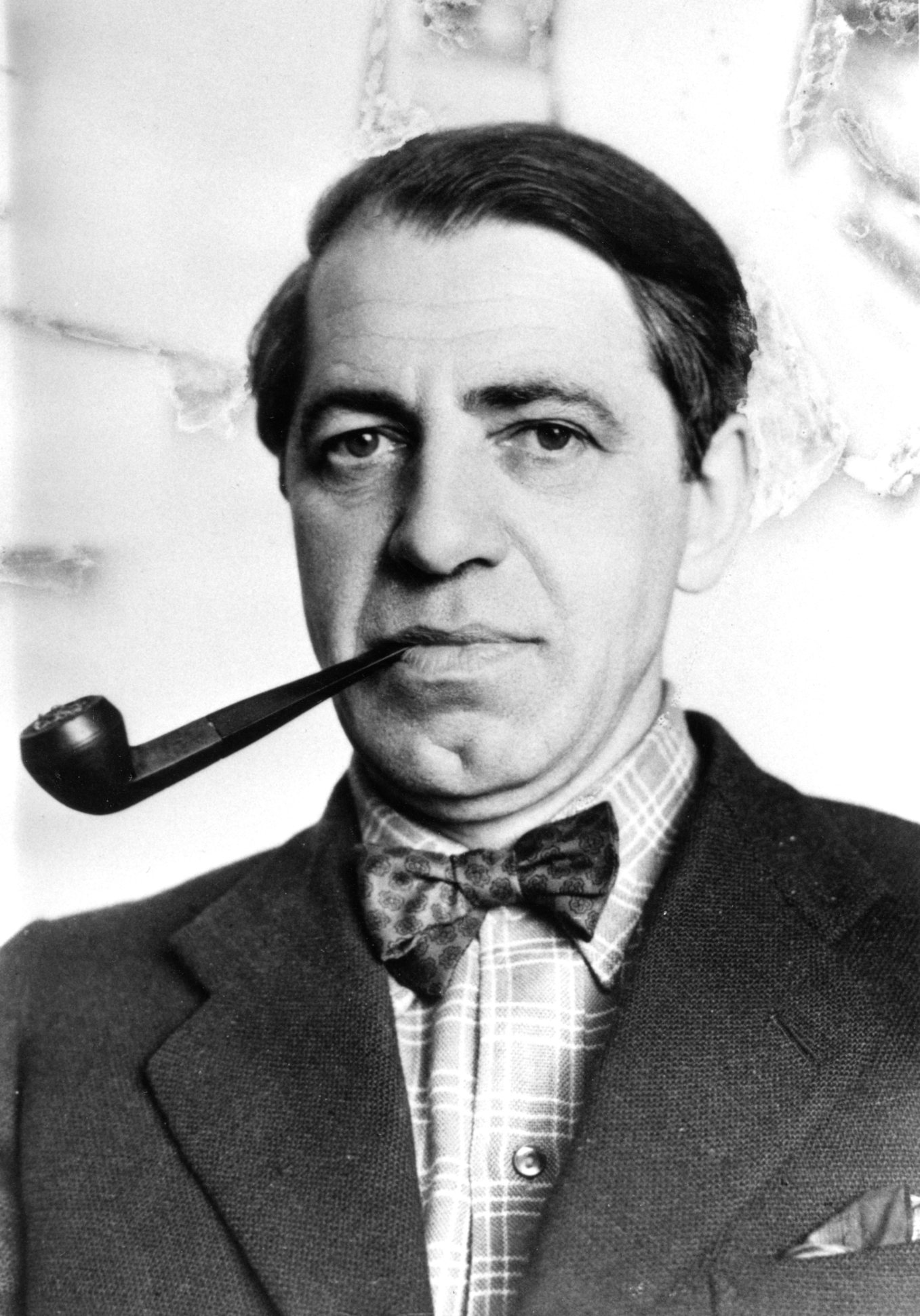

Stephen Gooden in the 1940s

Stephen Frederick Gooden was born on 9th October 1892 in Lambeth, South London. He was the fourth of six children and the only son born to Stephen Thomas Gooden (1856-1909) who in 1888 had married Edith Camille Elizabeth Epps (1868-1954). Two of Stephen’s five sisters died in infancy and none of his three surviving sisters married or had children – a legacy of the First World War. Only one lived to old age.

Gooden’s father was a respected and successful art dealer and print publisher with premises on Pall Mall in London who had joined in partnership in 1903 with Frederick William Fox (1857-1934), another art dealer. Their company, now called Hazlitt, Gooden and Fox, currently holds the Royal Warrant as Fine Art Dealer to Queen Elizabeth II.

In 1909, when Stephen was 16 and had just left Rugby School, his father died in a tragic accident aged 54, after he had fallen 30 feet from the bathroom window of the family house on Tulse Hill in South London. A few weeks later, then aged 17, Stephen enrolled at the Slade School of Art, where he studied for four years. At the start of the First World War he enlisted in the army and served for four years as a Private in 19th Royal Hussars (Queen Alexandra’s Own), a cavalry regiment. Gooden was a member of a team of three mounted men that supported communications between trenches. In 1918 he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps and started to learn how to fly, but the war ended before he could qualify.

Engraving

After the War ended Gooden struggled to make a living until about 1923, when he was given the engraving tools of his grandfather, the wood engraver William James Linton (1812-1897). Gooden had designed a few etchings in about 1919 and was known to sketch designs for his engravings using drypoint onto the copper plates that he preferred, but it soon became clear that he had skills as a pure engraver on copper. This is a method in which a burin, a steel tool with a broad wooden handle to apply pressure to the metal, is pushed slowly across a copper plate to cut a fine v-shaped groove into the surface. The width of the burin and the depth of the groove determines the amount of ink that is taken up by the design when the plate is coated with ink. When the plate is wiped to remove excess ink from the unengraved surface and pressed onto damp paper, the ink in the grooves is transferred to the paper creating an image in reverse of the design engraved on the plate. This means that any lettering must be engraved in reverse on the plate. Because copper is quite soft, after the design has been completed the plate is often coated electrolytically with steel to make it harder, so that more proofs can be printed from the plate. Engraving is a very slow process, as Gooden’s plate entitled Boy and snail indicates. The process of printing one proof at a time by hand is also slow.

Books

Gooden’s skill as an engraver was first employed by the Nonesuch Press, which had been founded in 1922 by Francis Meynell, a poet, and David Garnett, a writer and publisher. They published several fine, limited editions of books with a decorated title page and illustrations engraved onto copper by Stephen Gooden. Books such as Anacreon (1923) and a fine edition of the Bible in four volumes with The Apocrypha (1925-27), were highly sought after by bibliophiles in the late 1920s and 1930s. Printed by hand on hand-made paper and bound in gilt vellum bindings, some of these editions now sell for four figure sums. Gooden later engraved illustrations for books published by George Harrap & Co., including a fine limited edition of Aesop’s Fables (1935) with typically imaginative designs.

Bookplates

In 1923 Gooden received his first commission for a bookplate, a design for a keen patron of his work, an insurance executive named John Napthali Hart. This began an important type of personal and institutional commission for engraved labels to be glued inside books to mark their ownership. Between 1923 and 1954 Gooden designed 42 bookplates including three designs of different sizes in 1937 for the Royal Library at Windsor, and later engraved individual designs for Queen Elizabeth and both her daughters, Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret. One of the designs for the Windsor Library was modified for the new George Medal in 1940 and in 1942 Gooden was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the June honours list for his service to the Royal family.

Recognition by his peers

Gooden’s skills as an engraver had been recognised in 1933 by the Royal Society of Painter-etchers and Engravers when he was elected as a Fellow, and in 1937 he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy. He was made a full Royal Academician as an engraver in 1946.

In 1925 Stephen Gooden married an Irish poet and librarian, Mona Steele Price (for whom he designed a bookplate). They lived for three years in Upper Gloucester Street in London before moving for three years to Bishops Stortford, where he had studio in a large wooden shed next to his house. Gooden moved back to London in 1933 to rent a studio on Glenilla Road in Belsize Park, but there was no accommodation, so the couple lived nearby. It was perhaps this separation of home and studio which led them to move out of London again, their last move, to Chesham Bois, in 1939, where Gooden created a fine studio in which he could work. They lived there until Stephen's death in 1955.

The Second World War began some five months after their move to Buckinghamshire, when Stephen was 46. He was too old to re-enlist in the Army so he joined the local Home Guard, for whom he became a local commander for a while until it became too demanding, and he continued to work as an engraver. The market for fine editions of books had been dampened by the Great Depression of the 1930s, but almost disappeared during the war as it was hard to get high quality paper for printing copper engravings and there was little demand for such books. But Stephen Gooden had already diversified his interests.

Banknotes

In 1931 he had been selected by the Bank of England to advise the Royal Mint on the design of banknotes, a position he held until his death in 1955. In the early 1930s he designed a new £1 and 10 shillings banknote, neither of which were used. In fact, it wasn’t until 1957, two years after he had died, that one of his designs – the first coloured British £5 note – was issued by the Bank of England. The front of this note featured the head of Britannia wearing a high-plumed helmet and, on the reverse, a magnificent lion with in its mouth a ring attached to a chain and large key. This striking banknote was withdrawn in 1963 and ceased to be legal tender in 1967.

Gooden was also retained by the security printers Bradbury Wilkinson and Company, to help design currency notes for other banks and countries. Gooden’s designs were included on banknotes printed for the Bank of Greece in 1944, after the country had been liberated from German occupation and, in order to end hyper-inflation, needed new bank notes with many fewer digits. Gooden also designed banknotes for the Commercial Bank of Scotland, including a new purple £1 note in 1947 and a design which was used for the £5, £10, £20 and £100 notes; and some of his designs were used on new banknotes issued in 1949 by the Reserve Bank of South Africa with denominations from 10 shillings to £100. Gooden’s engraving of a ship, an Amsterdam flute, which was shown at the Royal Academy in 1953, was used on the reverse of the South African £5 note, which later became the 10 Rand note.

Both the Bank of England and Bradbury Wilkinson paid Gooden an annual retainer plus a fee for his designs, even if they were not used, so he was quite well remunerated. This was in contrast to the British Post Office, which offered a fee of £15 to artists who were asked to submit a design and engraving for a new stamp. If the design was used the artist would receive another 50 guineas. Gooden was asked to submit a design in June 1937 for some new high values stamps for George VI, but his design was rejected and led to an acrimonious dispute. In 1946 Gooden did not take up a request to design a stamp to celebrate victory in the Second World War. This was at a time when he commanded a fee of about £70 for designing and engraving a small bookplate.

Coats of arms

As well as designing armorial bookplates, Stephen Gooden also engraved coats-of-arms for the newly formed British Council in 1941 and for the Institution of Mechanical Engineers in 1947, an engraving which he used as his Diploma plate for the Royal Academy. A coat-of-arms he designed for Queen Elizabeth in 1950 was made as a tapestry to display at her Scottish house, Glamis Castle.

Gooden mixed his Royal commissions with designs for local societies and schools, such as award labels for the Hertfordshire Art Society (1938) and for Ashwell Primary School (1942), also in Hertfordshire. One of his last designs was for an engraved ‘device’ for the Griffin Club in Amersham in 1947, probably commissioned by one of its members. This was used on the club members’ booklet and shows a typical Gooden design: a nonchalant Griffin with legs crossed, leaning against a shield (engraved with the date of the club’s foundation) and a stake with a pennant flying above with the club’s motto ‘Clam Prodesse’, meaning ‘Secretly benefit’.

Stephen Gooden’s last illustrated book was published in 1946, a collection of poems about cats selected by his wife, Mona, and issued in a limited edition of 105 copies, signed by editor and artist. There was also a trade edition.

Last years

Stephen Gooden was diagnosed with colon cancer in 1953 and underwent two operations, but continued to work on his design for the new £5 note and for bookplates for Lord Fairhaven and the Royal College of Surgeons. He died at his home in Chesham Bois on 21st September 1955, aged 62. His wife, Mona, died about three years later in July 1958, aged 63, of lung cancer. They had both been heavy smokers. They had no children.

Stephen Gooden helped to revive the slow art of copper engraving and hand-printing in a period when advances in photolithography were enabling art to be easily published and mass produced. His work was always on a small scale, rarely more than about 150 mm in height, often much smaller and commonly circular in aspect, but he was able to achieve an effect of distance by varying the depth of his engraved line and create three dimensions and depth by subtle cross-hatching. His lions are impressive beasts; his horses are drawn with an understanding of how they move; and his dragons are fierce. There is no better example of his skill as an engraver and his fertile imagination than the engraving entitled Triton (1940): the front quarters of a horse with clawed hands rather than hooves are merged with the tail of a reptile curved in shallow water to create a fabulous rampant creature ridden by a naked man wearing only a helmet, blowing though a spiral shell and holding, with the Triton’s reins, a trident and shield made of the carapace of a crab. It is a small masterpiece of the engravers art and a wonderfully inventive design.

Reference

Campbell Dodgson (1944). The Iconography of the Engravings of Stephen Gooden. London: Elkin Mathews.