Short biography of J.L. Carr: pupil, student, teacher and sportsman

(Last updated 26th May 2021)

Joseph Lloyd Carr (JLC) was born on 20th May 1912 at No. 5 Railway Houses at Carlton Miniott, a village outside Thirsk in the North Riding of Yorkshire. It was one of the row of houses facing the railway line here, because it is illustrated in Visions Afar, the Journal of Raymond Carr (1905-2005), his elder brother. Raymond's journal contains pictures of other houses in which they lived, so I have been able to identify them on Google maps and have provided links here, for the curious.

JLC's father was also named Joseph, so most of his family called him Lloyd. This middle name had been suggested by his mother's brother, Richard Welbourn, in honour of the Welsh Labour politician David Lloyd George (see Visions Afar). JLC also had two older sisters: Ethel Blanche (1900-1986) and Kathleen Winifred (1902-1999). Uncle Richard had also proposed that Ethel should be named 'Ladysmith', as she was born on the day that Ladysmith was relieved during the Boer War. Another brother, named Robert Wilfred, had died of meningitis aged four in August 1902. Joseph Carr senior worked on the railway at Thirsk Junction, which was a 5-minute walk from their house, where he was Night Stationmaster. It was a busy station in 1912, where nearly 400 people were employed.

Carr's first school was in the main village of Carlton Miniott, about a mile from his home. It is the only educational institution that he attended that is still there in name and in the same building, even if it has expanded. Carr wrote in notes cited by Rogers (2003): I scarcely can believe that, from the age of 5 until we left Carlton Miniott when I was about 8, a better education could have been purchased. I wanted information, and it was provided. I preferred order, and there was order. I needed others to emulate, and they were there. I was learning all the time. Carr published an article on his Headmaster, James Milner, in 1987.

The Wesleyan Chapel, which JLC attended on Sundays to hear his father preach, is now an evangelical church.

The old building of the primary school in Carlton Miniott as it is today.

Carr's family left Carlton Miniott in 1919 (according to RWC) or 1921 (according to JLC) when he was about 7 or 9 years old and moved to Sherburn-in-Elmet, situated on a ridge above the vale of York, not far from Leeds in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Carr's father was employed at the huge railway marshalling yard used by six collieries situated at Gascoigne Wood.

The Carr family first lived in a row of Victorian houses, then called Ashfield Terrace, in Low Street here and Carr was enrolled in the village primary school. The main entrance to the Hungate Primary School is shown to the left, through the arch. The telephone kiosk was designed in 1921, so it is contemporaneous. The history of the school is described here although the teacher, Mr. Potts, is remembered by Carr, so probably returned to the school after the war. Carr recollected the poor education and brutality of the school, something that may well have affected his attitude as a teacher, for he forbade the cane when he was Headmaster in Kettering.

The main street of Sherburn-in-Elmet, where Carr lived from about 9 y of age.

On the left, further up Finkle Hill is a sign for England's, a general shop, bakery and post office. This shop was owned by John England whose daughter Margaret married Raymond Carr in 1930 and whose son Tom married Kathie Carr in 1935. This is what Finkle Hill looks like today; the phone box has gone and John England's shop is now an optician. The village primary school is in new buildings.

Several of Carr's experiences in childhood were used in his novel A Month in the Country. Carr's father was a Methodist lay preacher, so the Ellerbeck family was based on his own, although he wrote in a copy of the novel that he gave to his sister Kathie, that Cathy Ellerbeck wasn't her. The trip to buy an organ was based on his sister's experience, something that JLC described in an interview recorded as a part of the Writers in the Region series. Raymond Carr in his Journal describes an instance in which JLC fell off a wall into a sewage pit, an event that does not appear in any novel.

The Carr family eventually moved into a house called 'Glencoe' on Low Street adjacent to the Methodist Chapel that the family attended, both now demolished. The house comprised a shop and, above it, a large room with a big wndow overlooking the street that they made into a tea room (see left). Carr's sisters, who had both lost their jobs, were employed in the tea room and sold bread and cakes from the shop below. This business probably helped to pay for Carr's education because, when he failed the entrance examination to Tadcaster Grammar School and would have remained in the primary school until he was 14, his parents decided to send him to Castleford Secondary School as a fee-paying pupil in the summer of 1925, aged 13. The school was 9 miles away, so Carr had a 2-hour journey on foot every day to and from South Milford station, then changed trains at Garforth to get to Castleford.

The Carrs' tearoom in Sherburn-in-Elmet and the Methodist Chapel.

The Headmaster of Castleford School was a man named Thomas Robert Dawes, who was a great influence on Carr, not just in terms of his personal education but in his educational methods, which were innovative by the standards of the day: he banned the cane and discouraged competition between pupils, something that Carr did too when he became a Headmaster. Dawes and his wife arranged pageants that paraded through the town involving local people as well as school children, and took parties of students to Germany to put on plays in schools there. He also welcomed school parties from Germany to visit Castleford. In the entry on Nicolas Breakspear in Welbourn's Dictionary, Dawes was described as mildly anarchic

. Carr gave a talk about T.R. Dawes on the BBC Home Service in September 1966.

Carr started writing while at the school, a magazine called The Torch which he composed and illustrated by hand. There was one copy, which he charged people to read (Rogers, 2003). He also acted. The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer reported on 20th December 1929 that the pupils of Castleford Secondary School had performed A Midsummer Night's Dream

under the direction of Mr Rankin, Carr's English teacher: Among the most succesful of scenes were the clown episode, J.L. Carr as Bottom being especially good. The sets were designed by JLC's art teacher Miss Gostick, who taught him about church architecture. JLC was 17 years old. Nearly 10 years later, in 1938 while teaching at Huron High School in South Dakota, Carr directed a performance of A Midsummer Night's Dream

, which was reported in The Evening Huronite.

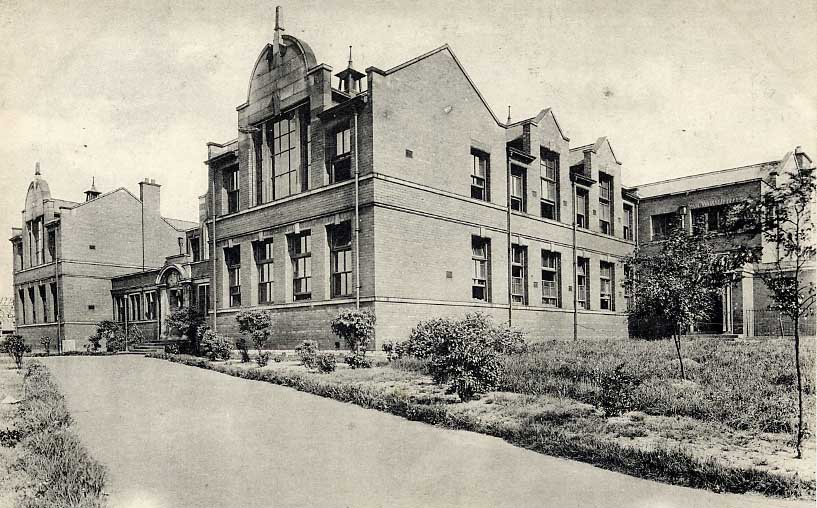

Castleford Secondary School, which Carr attended from 1925-30.

Carr also had some success with writing. A few days after his acting had been reported, on 9th January 1930 the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer gave news of awards to local people in a national scheme promoted by the Royal Institute of British Architects: Another Yorkshire success is that of J.L. Carr, of Castleford Secondary School, whose essay on Sherburn-in-Elmet Parish Church has been highly commended. The church is a Grade 1 listed building which dates from around 1100.

In his final year at Castleford at the age of 18 y, Carr applied to study at Goldsmith's College in London to become a teacher but was rejected, purportedly because when asked why he wanted to be a teacher he replied that the profession offered plenty of time for other pursuits. Carr then had to wait a year before being able to study and took a job meanwhile as a Supernumary Teacher at the Primary School in South Milford, 30 minutes walk from his home. The headmaster was a man named Captain Legatt, who beat his pupils, much to the dismay of Carr. There Carr played football for South Milford White Rose, a local team that did very well in a local football tournament called the Barkston Ash Cup. There is a grainy photograph of the team in Don Bramley's memoirs. The last game in this competition is described by JLC in a dedication to Tom England inside a copy of his novel How Steeple Sinderby Wanderers Won the F.A. Cup. In this novel Carr extrapolated the notion of success by an inspired village football team. Sinderby is a village four miles from Carlton Minniott, near Thirsk, where Carr was born.

Carr was accepted by Dudley Training College for Teachers and started on a two-year course in September 1931, aged 19 y. It was a mixed college with almost as many women as men, an unusual ratio for those days. The women lived in a hall of residence on the site of the college while the men lived in another hall in town, or in lodgings. At Dudley, Carr became Secretary of the Dramatic Society, ran in the College cross-country team, played football, and in his second and final year, edited the student's annual magazine called The Eagle. He was also given a new new name, apparently because fellow students thought that the J in his initials was for Jim. He must have liked this because he adopted the name and eventually became James Carr, the name he used on the spine of What Hetty Did.

Dudley Training College, which Carr attended from 1931-33.

Carr graduated in the summer of 1933 and found a job teaching English Literature and games at Thornhill Primary School in Bitterne, a village near Southampton in Hampshire, now a suburb of the city. He lived in digs at Thornhill Park Road, played football in the winter for Botley F.C. and cricket in the summer for Curdridge Cricket Club.

Carr spent two school years in Hampshire, from 1933 to 1935, but didn't seem to like it much. After less than a year, in February 1934, he told his sister that he was going to write to the Principal of Dudley Training College about his prospects of finding a job in Birmingham. The midlands of England seemed to appeal to him. Carr moved back and worked as a supply teacher in schools in Birmingham for the three school years from 1935 to 1938 while playing cricket for Aston Unity CC, mostly for the Second XI, batting at number 3. In 1938 he accepted an offer to exchange positions with Mary Elizabeth Kelly, a teacher at the High School in Huron, South Dakota, a small town on the prarie, almost in the middle of the United States, in terms of longitude at least. There is no evidence that he played cricket there.

Carr travelled for 8 days to reach Huron by ship and train (some of which is described in The Battle of Pollocks Crossing) and started teaching in September 1938. You can read about things that he did at the High School in the pages of The Evening Huronite

, the local newspaper here. Carr left Huron at the end of May 1939 and visited his Uncle Jim Welbourn (1865-1943) in Parma, Idaho, before taking a third class passage in a ship from Seattle to Yokohama in Japan. He then visited Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, Port Swettenham and Rangoon before presumably taking a ship to a port in India. Carr described all these places in letters sent to Jim Lusk, the editor of the local paper, The Evening Huronite, which printed them. The letters describing his journey to and across India have not been found, but he bought a camp bed in Karachi and travelled on the deck of a ship up the Persian Gulf to Basra.

Huron High School, taken from The Tiger, the school Yearbook of 1939.

In Iraq he visited the bibical cities of Ur and Babylon, where he found out that Britain had declared war on Germany. He hastened back to Europe overland through Beiruit and then by ship to Marseilles. He spent a few days in Paris before catching a boat train back to London. He voluntered to join the Royal Air Force and returned to Birmingham to teach while he was waiting to be called up. There he acted as an Air Raid Warden and taught in a number of schools, many of which had lost their teachers to national service. In one secondary school he taught handwriting to children and wrote short impromptu poems for them to copy from the blackboard. These he printed in mimeograph in about 1966 as The Battle of Birmingham, probably his rarest publication.

Carr spent almost six years in the RAF, initially as an Aircraftman photographer in an aerial reconnaisance squadron based in West Africa, an experience which provided him with material for A Season in Sinji and where he designed his first map, of England and Wales. He was promoted to Leading Aircraftman in October 1943 and was formally commissioned in April 1944 as a Flying Officer in RAF Intelligence. On his 45th birthday in May 1957 the London Gazette recorded that he was one of a number of Flying Officers allowed to retain the rank of Flight Lieutenant.

In April 1944 JLC met a Red Cross nurse named Sally (Hilda Gladys) Sexton (1919-1981) at a Ball at Doon House in Westgate-on-Sea in Kent, an event which is noted on one of his maps of Kent. They were married in the Methodist chapel in Elmstead in Essex, where Sally's parents lived, on 14th March, 1945. In January 1946 JLC left the RAF and after three months of demob. leave spent near Ravenscar in Yorkshire, quite near to the railway station where his brother was Stationmaster, he returned to Birmingham to teach. Their son, whom they named Robert Duane, was born in November 1947.

Back in the Midlands, Carr joined Birmingham Municipal Cricket Club and contributed material for the new Midlands Cricket Club Conference Yearbooks, the first of which was issued in 1948. He was mentioned as a player in the Yearbooks of 1950, 1951 and 1952, which recorded the achievements of the previous season. In the autumn of 1951 Carr moved to Kettering, to become head of a new primary school called Highfields, which was being built. While he waited for construction to finish he taught at a nearby primary school. The Carrs moved into a newly built house at 27 Mill Dale Road probably in 1952, perhaps the first that they had owned, where he was to remain for the rest of his life.

Carr joined the local cricket club in Kettering and played for their Wanderers XI, as there is a photograph of him in the team in 1954, reproduced in the Centenary booklet of the club. In 1956, with the help of local cricket club Secretaries and his wife Sally, Carr compiled statistics for the 10 clubs in the local league since it had been founded in 1951 and compiled a Yearbook for the Northamptonshire County Cricket League. In the first yearbook he announced that he would be gone the following year as he had obtained leave of absence to return to Huron to teach again at the High School, taking his wife and 9 year-old son with him.

In Huron in 1956 JLC found the notes of the local historical society that he had attended in 1938-39. He edited them and made many drawings of items used by the first settlers in Huron in the 1880s. Carr transferred the text and drawings by hand to stencils and printed the pages by a mimeographic process to create a booke he called The Old Timers. Eighty-two copies were either given to friends in Huron or he sold them to local libraries.

Carr's house at Mill Dale Road, Kettering, photographed in 2008.

Carr returned to teach at Highfields Primary School in 1958 and continued to edit the County Cricket League Yearbooks until 1961, when he gave it up. Perhaps he wanted to focus on his paintings of buildings and places that he eventually called The Northamptonshire Record. But his appetite for editing returned in about 1963 when he took over the production of the Northamptonshire Teachers' Magazine, for which he had written an article on his return from Huron. Carr renamed it in 1965 for the National Campaign for Education and the name stuck - the Northants Campaigner. This 20 page magazine was published twice a year, except for the last issue, and was given free to all teachers in the county. He used the magazine to make pointed comments about the lack of investment in primary education and to campaign against the 11-plus examination and streaming, amongst other things. Carr also wrote a mimeographed newsletter for parents of his school which he called The Termly Highfielder.

Carr's first novel, which he had started to write in the early 1960s after attending a course on novelists of importance organised by the Workers' Educational Trust, was published in 1963. He published his first small book in 1964, of the poems of John Clare, and designed his first published map, of Northamptonshire, in 1965. This was the start.

In June 1966 the Kettering Evening Telegraph reported that James Carr, Headmaster of Highfields School . . . is to leave at the end of this term to conduct two years’ research into integrated studies

. Although the report said that he was guaranteed a position until September 1969, he did not return to teaching, even though he continued to edit the Northants Campaigner until 1970. Carr had started to publish more of the small books and maps which are featured in this web site and which provided the bulk of his living.

Carr's last school, where he taught for 15 years except for a year in Huron, is now a member of an educational trust and was rebranded Greenfields Primary School. Carr continued to teach now and again, such as a lecture at the Department of Adult Education of the University of Leicester which he called How to write your own novel (in one easy lesson)

for which participants were charged £1. He was also invited to speak at Oxford University and at the J Pierpont Morgan Library in 1983, when he presented a manuscript of A Month in the Country. It is written on the back of English county maps.

Carr retained an interest in cricket and scored his last century in 1969, aged 57. He continued playing cricket for another 10 years while writing gentle, funny and wistful novels, designing elaborate maps, writing quirky dictionaries, promoting the designs of engravers, painting in watercolours, trying to preserve churches, carving old stone lintels into figures of biblical saints, and publishing little books of poets and authors whose work inspired him (and were out of copyright). He was a remarkable man.

For information about Carr's life as a writer you should read Byron Rogers' biography The Last Englishman (Aurum Press, 2003).

Honours and awards

- Christmas Short Story Competition, The Birmingham Weekly Post, December 1937, 1st Prize.

- Northern Arts Award of £100 from the North-East Arts Association for his novel

A Day in Summer

on 25th March 1966. - The Guardian Fiction Prize for

A Month in the Country

in November 1980. A Month in the Country

was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1980.- Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in April 1981. According to the RSL he resigned in 1984.

- Awarded an Honorary Degree of Master of Arts by the University of Leicester at a Degree Congregation on Wednesday 19th May 1982.

The Battle of Pollocks Crossing

was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1986.- Awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters in 1992 by the University of Huron (1883-2005).